I am still hard at work on the next iteration of my graphic novel, but I have been sidetracked by our return to France. You can read about that here:

In the meantime, I wanted to share this piece from the NY Times Ethicist column - Should You Be Allowed to Profit From A.I.-Generated Art? I am pasting it in its entirety at the bottom of the page since it is paywalled, but here is the gist of it (BTW, ChatGPT summarized the article for me, which I find to be one of its most convenient uses):

SUMMARY: The article addresses the ethical and economic questions surrounding the use of AI to create art. A reader raises concerns about purchasing AI-generated artwork for a tabletop game, feeling that it might be unfair to human artists. They argue that AI-generated art may be based on styles from other artists and question if it is right to profit from such creations. The Ethicist responds by noting that artists, including human ones, have historically borrowed and adapted from others.

AI systems, like human artists, learn from previous works and generate new content. The analogy is drawn between AI systems and human artists studying past masters. The piece also addresses concerns that AI could devalue human-made art, but points out that reproduction methods have long existed, and despite mass reproductions, original works retain their aura and value.

My thoughts:

I particularly enjoy the writer’s use of the phrase “centaur models” to describe “collaborations between human and machine cognition.” Might I also suggest “spork models,” “skort models,” or perhaps “cronut models?”

Regarding the Ethicist’s response, I was an art history major in college and I have heard these arguments throughout my life. I had to read The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction by Walter Benjamin, and my strongest memory is having NO clue what he was on about (give me a break. I was 19).

Many creative methods have been used during my lifetime that would have been anathema to artists of the past, such as Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop. Should artists not be paid because they used these programs? People were afraid that photography would be the end of painting and drawing, and then one day photography became its own art form.

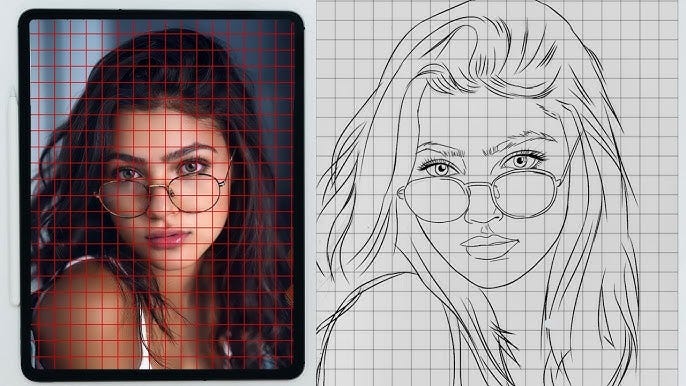

We watch a British TV show which I adore called Portrait Artist of the Year in which amateur artists are chosen to paint famous Brits. Many of the artists take a picture of the subject on their iPads and then layer a grid on top of that image. The judges do not discourage this. They accept it as part of a modern process.

Is a grid not just a mathematical tool to make the job easier? And what is AI if not an extremely sophisticated mathematical tool?

I use an AI app to create images and another app to lay them out into a graphic novel. The tech has allowed me to create the work in real time and release chapters every two weeks, a schedule that neither I nor a professional artist could have matched even two years ago. AI has allowed me to take my existing skill as a professional writer and expand into a medium and format that were formerly unavailable to me.

Any schmo can download Photoshop, but how many people do you know who can truly use it to its full potential? Within my own circle, those people are all professional graphic designers. I have owned Photoshop for years and have never gotten further than sticking my face on someone else’s body.

Greater and faster tools do not an artist make. AI is not creating artists from nothing; it is offering a new medium for those already inclined to make something new and interesting in the world.

(Happy to fight about this in the comments section.)

FULL ARTICLE:

Should You Be Allowed to Profit From A.I.-Generated Art?

The magazine’s Ethicist columnist on the values and economics of art created via artificial intelligence.

My friends and I use a website for tabletop role-playing games (think Dungeons & Dragons). When making a character for a ‘‘Lord of the Rings’’ game, I found what looked to be the perfect piece online: a Celtic-looking warrior in the style of Alphonse Mucha.

We attempt to attribute art whenever we can, and anything that’s only for purchase we either avoid or pay for. This particular piece seems to be available only in an Etsy shop, where the creator apparently uses A.I. prompts to generate images. The price is nominal: a few dollars. Yet I cannot help thinking that those who make A.I.-generated art are taking other artists’ work, essentially recreating it and then profiting from it.

I’m not sure what the best move is. One justification for A.I. art is that humans create the A.I. prompts that produce the images, so the resulting pieces are novel works. That seems wrong. I could bring an A.I.-generated image that I like to a human artist and ask them to ‘‘rehumanize’’ it for me. But that doesn’t feel right either — Name Withheld

From the Ethicist:

There’s a sense in which A.I. image generators — such as DALL-E 3, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion — make use of the intellectual property of the artists whose work they’ve been trained on. But the same is true of human artists. The history of art is the history of people borrowing and adapting techniques and tropes from earlier work, with occasional moments of deep originality. Alphonse Mucha’s art-nouveau poster art influenced many; it was also influenced by many.

Is a generative A.I. system, adjusting its model weights in subtle ways when it trains on new material, doing the equivalent of copying and pasting the images it finds? A closer analogy would be the artist who studies the old masters and learns how to represent faces; in effect, the system is identifying abstract features of an artist’s style and learning to produce new work that has those features. Copyright protects an image for a period (and just for a period: Mucha’s work is now in the public domain), but it doesn’t seal off the ideas used in its execution. If a certain style is visible in your work, someone else can learn from, imitate or develop your style. We wouldn’t want to stop this process; it’s the lifeblood of art.

Maybe you’re worried that A.I. image generators will undermine the value of human-made art. Such concerns have a long history. In his classic 1935 essay, ‘‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,’’ the critic Walter Benjamin pointed out that techniques for reproducing artworks have been invented throughout history. In antiquity, the Greeks had foundries for reproducing bronzes; in time, woodcuts were widely used to make multiple copies of images; etching, lithography and photography later added new possibilities. These technologies raised the question of what Benjamin called the ‘‘aura’’ of the individual artwork. Our concern for the authenticity of a painting — is it really a da Vinci? — is connected with the idea of it as the unique product of a historical individual. Benjamin thought that mass reproduction would diminish the aura of the original. But zillions of photographic reproductions of the ‘‘Mona Lisa’’ haven’t deterred people from flocking to see the actual painting.

An aura can attach to reproductions themselves. The value of an ‘‘original’’ photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron is undiminished by its reproduction in books and magazines. Alphonse Mucha himself specialized in illustrations meant to be reproduced in quantity, and a poster that brought him to wide notice in Paris was created, in 1894, for a play starring Sarah Bernhardt; she had thousands of copies made of it. Collectors prize those old color lithographs. In the digital era, contrivances like ‘‘NFTs’’ (nonfungible tokens) have been used to secure a similar effect of scarcity and specialness. Don’t count aura out.

Don’t count people out either. As forms of artificial intelligence grow increasingly widespread, we need to get used to so-called ‘‘centaur’’ models — collaborations between human and machine cognition. When you sit through the credits of a Pixar movie, you’ll see the names of hundreds of humans involved in the imagery you’ve been immersed in; they work with hugely sophisticated digital systems, coding and coaxing and curating. Their judgment matters. The same might be true, on a smaller scale, of the fellow who sold you this digital file for a nominal fee. Maybe he had noodled around with an assortment of detailed prompts, generated lots of different images and then variants of those images and, after careful appraisal, selected the one that was most like what he was hoping for. Should his effort and expertise count for nothing? Plenty of people, I know, view A.I. systems as simply parasitic on human creativity and deny that they can be in the service of it. I’m suggesting that there’s something wrong with this picture.

I know there are a million Substacks out there and never enough time to read them all. I greatly appreciate you taking the time to read this one.

Recap is one of my favorite features in copilot.

My views are still developing on this, but my intuition says that generative AI is a form of theft that our copyright laws have not yet evolved to deal with. I don't know if I can prove that in an argument, but that's what I feel, so we'll see.

As an illustrator (who doesn't use AI), I think there are many differences between what artists do and what generative AI does. It's true, as the articles says, that "Alphonse Mucha’s art-nouveau poster art influenced many; it was also influenced by many." However, there is a danger here of reducing the artist to a sort of nodal point of influences, without any individual input - I suspect that's what Roland Barthes' "death of artist" means (though, like you and Walter Benjamin, I can't say I have an in-depth knowledge of the text...!). Artists are influenced by other artists, but they also develop their own independent voice and style - just look at the different directions that post-impressionism went in, although all those artists were influenced by impressionism. An AI, on the other hand, is not - strictly speaking - "influenced" by anything, because it has no independent vision that it is working toward. You could argue that the persion crafting the prompts supplies that, but there is a big difference between this sort of editorial or directorial relationship to the art, and that which an artist has to their work.

Now, perhaps you want to point to such examples in art and writing - Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons have a hands-off approach, and have skilled craftspeople to do their bidding. In Renaissance times, you had "studios" where trainee artists would chip in and finish off the maestro's work (Leonardo drew an angel for Verrocchio's The Baptism of Christ, I think). And in the literary sphere, James Patterson just comes up with the plots for his ghost writers to flesh out.

This is all true, sort of - and not. Hirst and Koons are conceptual artists that view the idea as the primary thing of worth (a point I disagree with), which nonetheless still relies on skill and craft for its effective expression. Verrocchio was himself no slouch with a paintbrush. And never having read a James Patterson novel, I can't with integrity comment on the quality of his output, but I suspect that his bottom line is not literary - and those chaps and chapesses currently doing the donkey work will be sharpening up their resumés at this very moment, if they have any sense, because AI is coming for their jobs.

So I think the idea that "AI is just doing what artists have always done" is facile, at best. It ignores what is really going on with artists - the development of a personal vision, the search for meaning and the exploration of human themes that actually mean something to them (love, mortality, etc), and the tussle with skill, technique and equipment, which will also feed into the form the piece takes - an artist's style is also determined in part by their limits (Erik Satie was no Debussy, but his limitations forced him down quirkier, more interesting avenues, I would argue).

By the way, I'm a huge fan of PAotY too! It's fascinating to see the different styles and approaches, which do and don't use iPads, gridding, etc. They never pick my winners though. :)